Time zones can be one of the hardest and most confusing sources of technical issues in modern software systems. In this article we’re going to go through some common rules of thumb for dealing with datetimes when architecting those systems.

First, a standard

The standard representation you should use for datetimes by default is ISO 8601. The ISO 8601 standard looks like this:

YYYY-MM-DDTHH:mm:SS±hh:mm

For a concrete example, the date and time that Marty McFly went back to the future was:

1955-11-12T22:04:00-08:00

There are obvious advantages to this standard. For one, it will natively sort lexicographically in any programming language. For another, it includes the time zone to apply maximum specificity.

But the most important advantage is that it is a standard, and if you stick to it whenever possible you will find your stack easier to develop as more and more programming languages integrate features to parse and format this standard natively. I’ve worked with ISO datetimes natively in the most recent releases of Python, Java, and JavaScript. It’s particularly nice on the frontend because it guarantees the user will see the appropriate time in their current time zone.

So, if the ISO 8601 standard is so great, why isn’t it commonly used in databases for its easy lexicographical sorting?

Why aren’t there time zones in SQL?

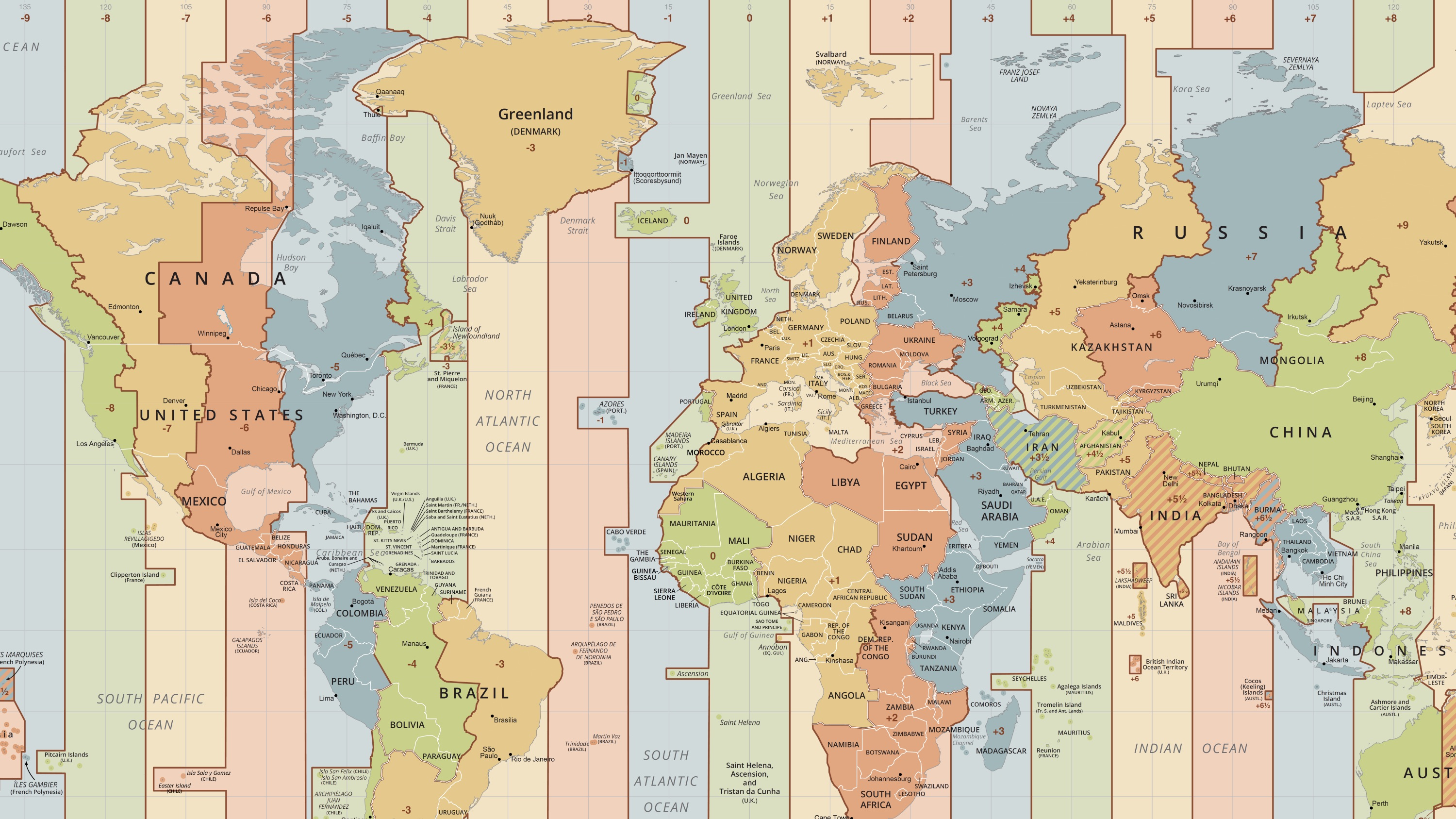

Time zones didn’t exist before common usage of railroads for transportation. Prior to the railroad every town and city would maintain its own local time, and travellers would readjust their watches when they arrived in a new place. But by the time railroads criscrossed North America, Europe, and Asia it became necessary to standardize local time across wide swathes of the planet.

In much the same way that the invention of railroads spurred the invention of time zones, the creation of distributed systems, microservices, and global internet businesses has spurred the adoption of time zone standards in software. However, some technologies were designed without these considerations in mind.

Before the invention of distributed systems most databases and the servers that ran them were colocal in the same time zone, often on the same computer. So basically, SQL (and often other database systems) broadly assumes that datetimes you give it are in the local time zone of the machine and that the software written to update the database is also in that self-same time zone.

For this reason when dealing with RDS systems it’s important to follow the following patterns.

- Whenever possible, pass datetimes to the service, module, or ORM that accesses the database with time zones attached. This will assure that no unwarranted assumptions are made between dislocated services.

- Set a standard and stick to it for what time zone the database uses.

Unfortunately it’s probably not in your best interests to include the time zone within the stored records of the database, this is because this would break the pattern SQL was designed to use, and for a legacy database require you do rather complex mass data operations to bring columns up to your new spec. (Daylight Saving Time begins and ends on different days every year, so it’s not merely a matter of adding the zone.)

Three DateTime Anti-Patterns

In this section I’m going to talk about some common errors regarding handling datetimes and how to fix them.

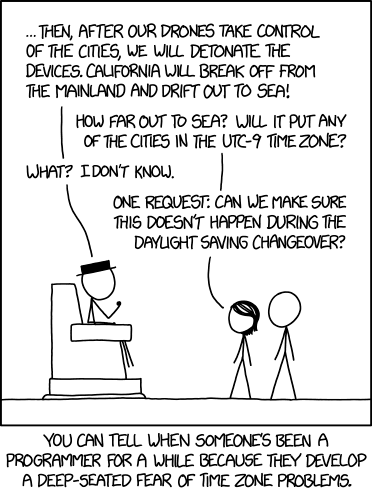

Datetimes are more complicated than even I am letting on here. But thankfully your friendly neighborhood library methods are here to help. The most complex time zone issues I’ve ever seen have involved multiple of the following sticking points.

1. An assumption was made about the zone of a datetime by one piece of a system that was not made by another

These issues can often be spotted with a little back of the envelope knowledge about your local time zone. For instance if you live and work in the North American Eastern Time zone (ET), and you notice that the datetimes in your database are all off by exactly 4 hours (or exactly 5, in the winter) then you might have a datetime being accidentally converted from ET to UTC.

2. Time zone conversion was done manually

This kind of error can serve to magnify the above error. Suppose you have one service that is operating in ET and a database that is storing UTC datetimes. You might think it’s sufficient to merely add four hours to the datetime, but this won’t work during the winter when ET switches from UTC-04:00 to UTC-05:00. Dynamically tracking when DST starts and ends adds additional complexity for you, because those dates are set every year (in the United States) by Congress.

And of course, if the client service is ever redeployed in a different time zone this code will now fail not just in winter, but all the time.

In general you should trust your programming language’s datetime representation to know what to do to correctly handle time zone conversions or other time difference calculations.

3. Time zones were dropped manually

Sometimes when dealing with frontend code in different browsers datetime formatting can cause unexpected errors. For instance, in most browsers the alternate form of the ISO 8601 standard YYYY-MM-DDTHH:mm:SS±hhmm (without the colon) is accepted, but Safari is not one of them. This leads some developers to haphazardly chop out the time zones, reducing the accuracy of data when viewing your webpage internationally.

This one should be a no-brainer in certain industries. For instance television, sports, and other live-streamed events absolutely positively need those time zones included for good user experience.

Final thoughts

- If you can, use ISO 8601 with the time zone when communicating between services.

- When writing database code make sure the DAO is in charge of deciding what time zone to store data in. Don’t rely on upstream systems to translate datetimes into the DAO’s time zone.

- Avoid writing code that manually does time zone conversions, always trust the language library to do this for you rather than broadly assuming you need to apply a specific offset.